How We Got Dumber: Why the Flood of Knowledge Fails to Make Us Learn

Everything that man does not know does not exist for him. Thus, each person’s universe is limited to the extent of their knowledge.

Albert Einstein

- Why is there a decline in general culture?

- Why, in an era where access to boundless knowledge is easier than ever, does humanity seem more disinterested in it than ever before?

- Why does the emergence of technologies (that allow absolutely everyone to learn more and better) actually turn the majority into dimwits?

Here is my reasoning. It is built on personal observations, extensive literature and years of discussion with young people (in the final years of higher education) and much older adults, from diverse backgrounds.

Accumulation of Knowledge

300,000 Years Ago

Since the oldest fossil discoveries in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, in 1960, it is believed that Homo sapiens, modern humans, have been walking the Earth for about 300,000 years. However, writing has only existed for 5,000 years.

To put it very simply, for 295,000 years, knowledge was transmitted orally. The accumulation of knowledge was impossible for obvious reasons. In the context of a nomadic lifestyle and living conditions (which we can’t even imagine today), the memory of ancestors—their survival techniques and early forms of belief—was passed down through songs and repetitive rituals. Additionally, a short life expectancy didn’t help the rapid development of knowledge either. As a result, human social organization remained quite primitive.

5,000 Years Ago

About 5,000 years ago, knowledge began to accumulate very gradually. To simplify again: halfway through this timeline, 2,500 years ago in Ancient Greece, Socrates (470–469 BCE) is said to have declared, “The first knowledge is the knowledge of my ignorance” (“I know only one thing: that I know nothing”). This implies that knowledge was already too vast and inaccessible in its entirety, even for the most erudite.

After 2,500 years of transmitting knowledge through writing, neither the capacity of the human brain nor the length of a human life allowed for grasping the entirety of accumulated knowledge. Even though writing techniques at the end of the Neolithic period (5,000 years ago), through the Copper and Bronze Ages (4,500 years ago), and into Antiquity (~3,000 years ago) were far from resembling a modern BIC pen on smooth white paper. Not to mention that the literate in each kingdom could likely be counted on two hands, and the price of books, even in the first millennium CE, remained accessible only to the clergy and nobility.

Chaotic Transmission in the Beginning

2,500–3,770 Years Ago

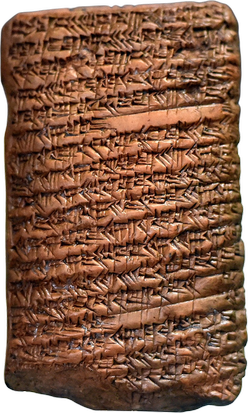

For example, this Babylonian clay tablet revealed that the Pythagorean theorem was actually known 1,200 years before the Greek mathematician Pythagoras (580–495 BCE). Dating to 1770 BCE, this tablet contains calculations using the famous theorem to determine the diagonal of a rectangle. Another tablet, from around 1800 to 1600 BCE, confirms that the Babylonians not only knew this mathematical principle but also understood irrational numbers, as evidenced by their calculations involving the square root of two.

Historians suggest that the school founded by Pythagoras in Ancient Greece greatly contributed to popularizing and spreading knowledge of this theorem, even if he was likely not its originator. Since no writings by Pythagoras himself have survived, much of what is attributed to him was passed down orally and credited to his name out of respect. Even if he wasn’t the first to discover the theorem, his influence helped anchor it at the heart of mathematics for millennia.

In fact, history is full of examples like this, where a well-known name is merely the mouthpiece (or, in today’s terms, an “influencer”) of a discovery or innovation.

The Beginnings of Exponential Growth

1,200–400 Years Ago

In the 2nd century CE, the Chinese invented paper, a secret they guarded jealously for several centuries until it eventually leaked along the Silk Road. The appearance of paper in the Middle East before the invention of the printing press sparked a surge in intellectual life. The 500 years following the start of paper production in the 8th century in Samarkand (a major center of knowledge) are known as the Golden Age of Islam. However, it’s clear that this center of knowledge didn’t reach the entire population of the region at the time.

Ulugh Beg, the ruler of Samarkand in the 15th century, who built three universities, is today primarily known as an astronomer who also constructed an observatory 200 years before Galileo invented the telescope. Ulugh Beg calculated a solar year with a precision that modern AI corrects by only 1 minute and 2 seconds.

It’s estimated that in the Middle Ages, there were up to 400 paper workshops around Samarkand, while Europe was going through its Dark Ages. Eventually, Islamic science and the paper it was published on made their way to Europe, laying the foundations for a scientific revolution.

600 Years Ago

In 1448, the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg (Johannes Gensfleisch, from Mainz, Germany) accelerated and simplified the dissemination of knowledge. This was followed (very gradually) by widespread literacy in Europe, thereby opening the Gutenberg Parenthesis (more on that later).

Thus, in a very recent period of human history, the accumulation and spread of knowledge literally exploded. It became possible to produce an entire book in 1,250 copies in just two weeks, whereas previously a scribe could produce only one book per year. Naturally, the price of books dropped significantly, making the printing press one of the most influential inventions in history.

Less Than 100 Years Ago

Over the last century, with digitization, we’ve witnessed an exponential accumulation of knowledge and information, the volume of which defies comprehension. One could even speak of an infinite accumulation of data, much like the infinite accumulation of capital, the absurdity of which I discuss in my book “Psychologie des (nouveaux) riches” (Psychology of the (New) Rich). While these are different concepts, their principle of infinite accumulation has emerged and developed in our era.

It might seem that the accumulation of data should be a positive thing. However, it’s crucial—especially in our time—to clearly distinguish between two fundamental concepts:

- Knowledge, and

- Information (or data).

Knowledge is something constructive, useful, and cohesive. Information (or data) is the general noise that comes and goes, replaced day after day by a new, incessant cacophony of “news” and “data,” like waves in the ocean. I won’t even delve into the utility of this data, including all debilities published on social media and beyond, with the sole purpose of its “creators” being to exist in the eyes of 8 billion of their peers.

The Internet has given stupidity a second life — in the past it was forgotten, now it is archived.

Umberto Eco

As early as 2018, it was estimated that 90% of the world’s data had been created in the previous two years (2016–2017). I’d be tempted to say, “imagine where we are now, nearly 10 years later,” but in reality, it’s impossible to fathom. Today, it’s estimated that humanity produces 29,000 gigabytes of data PER SECOND. This volume and density of data in such a short time is no longer conceivable for the human brain. To the point that this Big Data gives rise to new types of statistics. However, consider the tiny fraction of truly useful knowledge within this massive pile of data—so passionately praised by the high priests of digitization and AI, backed by their loyal army of useful idiots.

Yet, despite the endless stupidity of the masses and the constant propaganda published everywhere around the world, fortunately, the accumulation of true (and increasingly complex) knowledge continues.

Cultural level

Nevertheless, in the context of this conclusion, here is the corollary and the raison d’être of this paper. Humanity’s aspiration for self-development and self-improvement seems to be inversely proportional to the ease of learning and the growing expanse of accumulated knowledge. Let me put things into perspective.

The unprecedented ease of access to knowledge in history, the learning methods that are as engaging today as they were tedious 100–200 years ago, and the immense volume and quality of interdisciplinary knowledge accumulated nowadays should surely ignite a thirst for knowledge in most people and drive them to continually feed the brain of Homo sapiens—reflective, collaborative, innovative, and curious.

But artificial intelligence (which is supposedly meant to think for us) and the outsourcing of knowledge (storing knowledge on remote servers) create a paradox: Homo sapiens seems increasingly inclined to stop learning, under the pretext that all this knowledge is just a click away.

In the past, people lacked the opportunities, methods, and means to learn, so it’s almost natural that the majority remained illiterate and ignorant. But today…

Behind the virtuous facade that everyone is supposedly learning constantly, especially in schools, the reality is that the general culture of the masses declines year after year. Because sporadically finding answers through ChatGPT improves neither knowledge, nor neurons, nor memory.

Everything that man does not know does not exist for him. Thus, each person’s universe is limited to the extent of their knowledge.

Albert Einstein

Jevons Paradox

So, what do we have today? A question that hits hard…

Humanity seems to once again demonstrate the rebound effect, but this time in a different way. This paradox was described in 1865 by British economist and logician William Stanley Jevons:

as technological improvements increase the efficiency with which a resource is used, the total consumption of that resource may increase rather than decrease. Specifically, this paradox suggests that introducing more energy-efficient technologies can, in aggregate, lead to an increase in total energy consumption.

In simpler terms: an increase in consumption that exceeds efficiency gains. It’s a snake biting its own tail.

Now, two observations based on this rebound effect:

- First, data is to the digital economy what fossil fuels are to energy supply. The more we consume, the more we need/want. It’s a true junkie addiction. The corollary: AI is supposed to process the colossal amounts of data produced by 8 billion humans who can’t handle it themselves. Yet, this same AI generates data at a geometric rate, to the point where one could amusingly imagine a moment when even AI becomes overwhelmed by the overproduction of Big Data—the darling of progressivism and today’s economic model.

- Second, humanity seems to operate on a principle opposite to the rebound effect: the decline in its general culture (consumption of useful knowledge) is at the opposite end of the continuous accumulation of that same useful knowledge.

Not to mention that the accumulation of useful knowledge, as always, is only possible thanks to a thin layer of the population compared to the mass of Homo sapiens still roaming this planet.

The Wikipedia Effect:

knowing where to find info replaced actual knowing. A kind of neuroplasticity sabotage from algorithmic spoon-feeding.

The Gutenberg Parenthesis collapse theory (by Jeff Jarvis) suggests that the print era (1450–2000) was a historical anomaly—a parenthesis of:

- linear thought (books as a sequential narrative),

- authorship (fixed text and individual creativity),

- and deep reading (analysis, not scanning).

Digitization is bringing us out of these parentheses and back to a pre-Gutenberg world of:

- fragmented knowledge (TikTok/Instagram vs. books),

- oral culture 2.0 (memes, viral speech),

- dematerialization of text (hyperlinks destroy the “sacredness” of the book),

- erosion of authority (algorithms = experts).

Why it matters? The internet didn’t just change media—it unmade the cognitive habits literacy built over 500 years. Today, we’re post-literate, but not wiser.

Question: are we building libraries or crutches?

Here’s the digital age’s paradox: while the internet democratizes knowledge, it also immortalizes ignorance. Unlike pre-digital eras—where foolish ideas often vanished due to limited reach—today’s nonsense is algorithmically resurrected and amplified. Corollary: eternal misinformation with algorithmic fertilizer. Platforms reward engagement, not truth—making stupidity more contagious than wisdom. Historical irony: the tool meant to enlighten, simultaneously, catalyzes our (numerous) cognitive biases.

We are swimming in a true paradox of cognitive decline in the information age:

- The illusion of wisdom – Google and AI give answers but strip away the struggle that forges real understanding (the “Gutenberg Parenthesis” collapse).

- Attention as extinct resource – our brains now reward recognizing information over processing it.

- Cyborg dependence – outsourcing knowledge to a single click shrinks human memory to the capacity of a goldfish.

Deliberation

It’s obvious that in all eras, the majority of people didn’t strive to educate or improve themselves, just as the overwhelming majority today spends their free time consuming content devoid of any meaningful or intelligible substance. In other words, garbage content.

But why are we like this? Perhaps because today, useful knowledge is too polluted by the useless? Does this mean we’re more exposed to garbage data than to useful knowledge? Or maybe we can’t tell the difference between the two? Or is it because garbage (useless) data is easier and more enticing?

Is it possible to reverse this trend? Which, by the way, is no longer just a trend but a well-established fact. Or is humanity already lost, surrendering with abandon and carelessness on a slippery slope, where a complacent majority (which, by the way, will never read this article) indulges in ecstatic emotions through technologies that could instead foster their self-development—thereby reducing the surrounding mediocrity?

Can we still inspire today’s youth to learn in order to understand the ambiguities and complexities of the world around them, instead of aspiring to become influencers taking photos in private jets rented for 20 minutes just to show off on Instagram and TikTok? And why do their elders, who think things were better before and that today’s youth is a disaster, themselves consume just as much garbage content while dismissing true knowledge?

That said, the volume of useful knowledge (not data) today is so immense compared to the learning capacity and biological memory of humans that not only is it impossible to fully grasp it, but its relentless growth might discourage even the most curious and gifted individuals our species can produce.

So, perhaps, aware of this reality (while remaining unaware of their own laziness and carelessness), the “masses” no longer strive for continuous learning—to “become a better version of themselves every day,” as the saying goes. Especially since, apparently, AI is now here to do everything for us…

Moreover, the thirst for knowledge often stems from a desire (need) to control and understand everything immediately. Yet true knowledge requires patience (and thus time and perseverance), doubt, and the acceptance of not knowing (hello, Socrates).

Perhaps this is why some people want to develop microchips integrated directly into the brain? After all, maybe it’s the only way to pull the masses upward? The development of the human being as an individual through cyber-knowledge (in a cybernetic augmented reality)?

But what kind of knowledge? Considering that the prefix cyber comes from the Ancient Greek kubernao, meaning “to steer a ship,” and kubernēsis, meaning “the gift of governance”. And today, we define governance as transitioning a system from one state to another through targeted actions by the governing entity (while meeting certain optimization criteria)…